Technology Delays Hollywood's Retirement Age

Last November, Netflix successfully premiered the movie The Irishman, produced and directed by Martin Scorsese and based on Charles Brandt’s biography of Frank Sheeran called I Heard You Paint Houses. A star-studded cast tells Sheeran’s story. Sheeran, played by Robert De Niro, was a trucker who became a hitman for the gangster Russell Bufalino, played by Joe Pesci, and the union leader Jimmy Hoffa, played by Al Pacino.

Apart from this stellar cast, Scorsese chose the company Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) for production of visual effects (VFX) and computer-generated imagery (CGI). Founded in 1975 by George Lucas, the company has been responsible for or involved in creating the visual effects in some of Hollywood’s best-known super productions: Star Wars, Titanic, Jurassic Park, Harry Potter, Pirates of the Caribbean, Avengers, and many other blockbusters. This company is one of the US’s biggest VFX producers, turning over 450 million dollars a year. Even this striking figure pales into insignificance against the valuation of 259 billion dollars placed on the animation, visual effects, and video-game industry in 2018. It is also an industry that has been growing exponentially in recent years thanks to more affordable Internet access, the mass take-up of smartphones, and video on demand systems.

The truth is that maybe because it sits at the perfect, creativity-kindling intersection between art and technology, the visual effects industry is a constant source of innovation. To mention only some of many, prime examples include coloring video footage to give spring-like hues to scenes actually shot in January, fluid simulation to render water or explosions, artificial intelligence to animate an army of orcs in which each one has its own behavior, and motion capture technology to animate a virtual avatar.

In the case of The Irishman, ILM developed a groundbreaking system to make the actors look younger. For those of you who haven’t seen the movie, it takes place from 1949 to 2000 and is set at three different moments of the characters’ lives. At his youngest, for example, Pacino is 39 years old. Until ILM took on this challenge, there were two main technologies for making actors look younger.

The first involves creating a doppelganger using images of the actor’s face making different gestures. The Mova camera system is an example of systems of this type. Once the actor’s double has been generated it is superimposed over the actor’s image and the production team then animates the double manually, modifying its features. The downside of this system is that the acting tends to lose realism and authenticity, since it is the technicians who manually animate the virtual double rather than the actors actually playing the part themselves. The movie The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, starring Brad Pitt, was generated using this method. The whole process, involving a team of over 155 people, took two years to compete.

The second technology, like the first, starts with the creation of a virtual double of the actor, by scanning the face and then modifying it on the basis of performance capture. In this case, however, the virtual double is animated by the actor himself on the basis of their facial expressions. To do that, the actor is fitted with a motion capture device comprised of a helmet with several cameras focused on their face and with tracking dots all over their face. The camera device picks up the movement of these tracking dots on the face, animating the digital double accordingly. The downside of this system is that certain facial expressions are lost (tracking dot precision problem), so the acting suffers in quality. It also requires the actor to wear a helmet with several cameras during the shoot and having their face plastered with tracking dots, hindering the performance further. The recently released movie Gemini Man, with Will Smith, uses this system.

In The Irishman, Scorsese wanted his actors to be able to perform freely without having to wear cumbersome equipment or work with their faces covered in tracking dots, and without forfeiting a single detail of the actor’s performance. So, ILM set out to develop a new system comprising 1) a set of cameras affectionately dubbed the “three-headed monster” during the shoot, and 2) image processing software called Flux.

The camera rig has different components. At the center is a RED Helium 8k digital camera to record the video footage. On each side of it are two Alexa mini high-resolution ARRI cameras, modified to register only infrared light and synchronized with the central camera. These cameras are known as “witness cameras.” This system captures the actor’s facial performance from two angles, generating an infrared stereo image. The scene is also lit with infrared spotlights to prevent shadows in this spectrum; this light is invisible for the central camera. This lighting helps the witness cameras to capture the actor’s volumetric face data better without using tracking dots.

In addition to these three cameras, there is also a previous preparation process involving a LIDAR scanner to obtain the exact position of all the points of natural and artificial light, while the whole scene is captured in HDRI to obtain the light intensity and color of these points.

This whole data set is obtained for each frame of the sequence being shot and is then sent to Flux for processing. This software combines the infrared images with the real image, the scene lighting, and the shading to create a virtual mesh superimposed over the actor’s real face. This mesh is a geometric model of the actor’s face for each image and is used to deform the actor’s younger digital double.

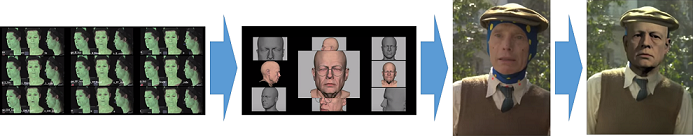

This digital double is created previously by two commercial systems 1) Disney’s Medusa for capturing hundreds of poses of the actor’s face, and 2) Light Stage software for capturing skin, texture, and porosity details. Based on the contemporary digital double, four models are then created for each actor at different ages. They basically paint textures, add or remove wrinkles, etc.

Although the Flux software is a brilliant specimen of data fusion, there is also a fair amount of post-production manual work to correct any discrepancies in the actors’ younger doubles. ILM created two new tools to help out in this manual post-production process.

First, a catalog or repository of images is built up from each actor’s film career with details of their nose, mouth, eyes, etc. This catalog provides a detailed reference bank that can then be used in post-production for phasing in “young” facial elements in the sequences where this is needed.

Second, a machine-learning tool was created to scan the repository and find the video footage or image most resembling the sequence currently being worked on, according to varied criteria such as: lighting, angle, eyes, etc. Swift access to these images helps the post-production team to correct any discrepancies generated by Flux.

One of the main advantages of ILM’s new system is that it is non-intrusive and can be used for close-up shots where performance capture is important, unlike other hitherto-used de-aging techniques, where the emphasis is on action. It also enables the scene to be shot with the actors naturally together on the set instead of on a special motion capture set or wearing special cameras with their face spotted with tracking dots.

You might not have liked the movie, and we all have our own views about Netflix’s methods to be able to take part in the Oscars, but ILM has undoubtedly dreamed up a new technique that is now here to stay. Who knows if further miniaturization and automation might be possible in the future and incorporated into our smart phones? It would certainly be the most widely-used filter on Instagram.

Author: Víctor Gaspar Martín